- Home

- Chris Grabenstein

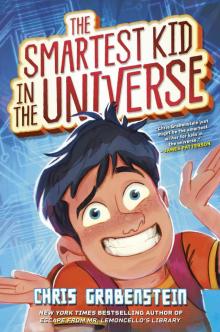

The Smartest Kid in the Universe Page 3

The Smartest Kid in the Universe Read online

Page 3

“I’m starving,” Jake grumbled, twisting the volume knob next to the video monitor to mute the sound. “Watching all those people chowing down in there makes it worse.”

“If you were that hungry,” said Emma, “we should’ve just nuked a frozen cheeseburger back home.”

“This is easier,” said Jake.

Emma shook her head and went into the bathroom.

Jake spied a glass jar of jelly beans sitting on the greenroom table.

It was a small jar with a wire-clasped lid. There were only about two or three dozen brightly colored jelly beans sealed inside. A small snack. Just enough for one hungry kid.

Just enough for Jake.

So, since Emma was out of the room, and since nobody had labeled the jar as theirs, Jake popped open the top and gobbled down the jelly beans, one fistful at a time.

They were pretty tasty. Not as good as Jelly Bellys, but definitely Easter basket–quality stuff.

By the time Emma came back into the room, the jelly beans were gone.

And even though he didn’t know it yet, Jake McQuade’s life was never, ever going to be the same.

Dr. Sinclair Blackbridge spoke after the dinner and dessert dishes had been cleared, after Jake and Emma had finished their delicious meals and headed for home on the uptown bus (without their mother knowing they’d even been at the Imperial Marquis for dinner).

As Dr. Blackbridge left the stage, he was mobbed by a crowd of eager admirers, all of whom wanted to shake his hand, congratulate him on his genius, have him sign a book, or ask a follow-up question.

One of those admirers was an intense young scientist and inventor named Haazim Farooqi, who had come to America from Pakistan to study biochemistry. Farooqi was only thirty-three years old, but he was a genius, even if nobody (other than his mother) knew it.

“Professor Blackbridge?” he cried out. “Professor Blackbridge?”

The MIT scholar pretended he couldn’t hear Farooqi.

“I know you can hear me, sir,” shouted Farooqi. “I’m speaking very loudly, and you’re only three feet away. The elementary physics of sound waves assures me that you are receiving my auditory signals.”

“How did you even get in here tonight, Haazim?” said Blackbridge as he scribbled an autograph in a book a fan had thrust at him.

“Well, sir,” said Farooqi, “I’m rather determined.”

“And I’m rather busy.”

“But, Dr. Blackbridge, sir, I’ve had a breakthrough! I think. I mean, I won’t know for sure until we run a series of rigorous tests.”

He finally had Blackbridge’s attention. “We?”

Farooqi beamed. “Yes, sir. You and me. Together we’ll make your most recent prediction come true.”

Blackbridge chuckled and shifted his focus to signing another copy of his book. “I’m a thinker, not a doer, young man,” he said without bothering to look at Farooqi.

The young biochemist wasn’t discouraged. “That’s why you need me, sir. I’m a doer. In fact, I already did it. It’s done. I left it for you. It’s backstage. In the greenroom, sir.”

“I’m not returning to the greenroom. My driver is waiting out front. I need to be at the airport.”

“But—”

“Call my assistant. We might be able to find some time for you on my calendar.”

“No, sir. I already called. Your assistant told me you’re completely booked. For the next ten years. Wait. Don’t leave. I’ll go grab my prototypes. You can take them with you. Maybe do your own research.”

“My car is waiting….”

“I know. I’ll be quick, sir. Trust me—you don’t want to leave this hotel without proof that what you just predicted can actually come true. Not in thirty years. Not in twenty. But tomorrow. Today!”

A fresh wave of well-wishers and glad-handers swamped Professor Blackbridge, pushing Farooqi farther and farther away. One of Blackbridge’s handlers was attempting to guide the esteemed theoretical thinker toward the exit.

Farooqi didn’t have much time.

He raced out of the ballroom and entered the kitchen.

He dashed into the greenroom to grab his container of samples.

He froze in horror.

His jar of jelly beans was empty.

His precious, one-of-a-kind, irreplaceable prototypes were gone!

Jake and Emma, their bellies full, rumbled back uptown on a city bus.

This one was a local, making all the stops.

Emma carried a white paper shopping bag filled with “leftovers” from their backstage banquet feast: an aluminum tray of cheese ravioli and two extra slices of chocolate mousse cake with raspberries on top.

“Emma, did you know that chocolate was introduced to France by the Spanish in the seventeenth century?” said Jake.

Emma shook her head.

“Chocolate mousse, which of course means ‘foam’ and not an antlered cousin of elk, has been a staple of French cuisine since the eighteenth century.”

Now Emma was staring at Jake.

“Raspberries, on the other hand, are believed to have originated in Greece. The scientific name for red raspberries is Rubus idaeus. That means ‘bramblebush of Ida,’ named for the mountain where they grew on the island of Crete.”

“What are you talking about?” said Emma. “How do you know all this stuff?”

Jake shrugged. How do I know this stuff?

“Beats me.”

The bus lurched to another air brake–hissing stop.

A family—a mom, a dad, and two kids—seated directly across from Jake and Emma near the back of the bus looked at a map and then at each other nervously.

“Hiki ndicho kikomo chetu?” said the mom.

“Sina uhakika,” said the dad, sounding anxious.

Jake smiled. “Unataka kwenda wapi?” he asked.

“You speak Swahili?” asked the somewhat surprised father.

“Of course he doesn’t,” said Emma.

“Ndiyo,” replied Jake. “Ndiyo, nadhani nafanya.”

The father, speaking Swahili, told Jake that their hotel was located on West Fifty-Ninth Street.

“Ah,” Jake replied, also in Swahili, “then you will need to exit the bus in two more stops.”

“Thank you, young man!” said the mother.

“Thank you,” said the two children. All of them were still speaking Swahili, and so was Jake.

“Karibu,” he said. “Furahia jioni yako yote.”

“What’d you just tell those people?” asked Emma.

“I said, ‘You’re welcome. Enjoy the rest of your evening.’ ”

“You speak Swahili?”

“I guess. I mean, I think I just did.”

“You can’t help me with my Spanish homework, but you speak Swahili?”

“It’s just something I picked up,” Jake said nervously. “And not from Kojo. His grandfather came to America from Zimbabwe, a landlocked country in southern Africa that’s bordered by South Africa, Botswana, Zambia, and Mozambique.”

Emma was gawking at her big brother as if he were a freak. Jake couldn’t blame her. The words tumbling out of his mouth were kind of freakish.

“In Zimbabwe,” he continued, “there are sixteen official languages, none of which is Swahili. Those official languages are Chewa, Chibarwe, English—”

Emma cut him off. “And how’d you know all that stuff about chocolate mousse and raspberries?”

“I don’t know,” Jake replied. His palms were starting to sweat. His stomach felt queasy, too.

HOW DO I KNOW THIS STUFF?

“Are you feeling okay, Jake?” whispered Emma, sounding seriously worried.

“Not really.”

“You’re sweating.”

“Yeah,” sai

d Jake. “I guess I shouldn’t’ve eaten the beef and the chicken.”

“You wolfed down two slices of cake, too. With extra chocolate sauce.”

Jake nodded. “I think I gave myself indigestion.”

“And that makes you know Swahili, African geography, and the history of food?” said Emma. “Usually it just makes me burp.”

“I need to go home and go to bed.”

“We should call Mom. You might need to see a doctor.”

“No. It’s just indigestion. Of course, indigestion, also known as dyspepsia, is a term that describes a wide range of gastrointestinal maladies.”

“Jake?”

“Yeah, Emma?”

“You’re scaring me.”

“I know. I’m scaring me, too!”

The next morning, Jake realized he probably should tell his mom about the weird stuff that started happening when he and Emma left the hotel.

But then he’d have to tell her he’d disobeyed her orders (again) and dragged Emma down to the Imperial Marquis (again) to mooch a free gourmet meal off the hotel staff (again).

So instead he sat quietly at the breakfast table and ate his cereal. When Emma gave him a worried look, Jake shifted his focus to the back of the cereal box and read about how Cheerios were “oatstanding,” and somehow he knew that Cheerios were originally called Cheerioats back in 1941, but the name was changed in 1945.

“What’d you guys do for dinner last night?” Mom asked, guzzling coffee.

“Nothing,” said Jake, because that was his go-to answer for all sorts of Mom questions.

“Seriously?” she said, raising her eyebrows. “You didn’t feed your little sister?”

“We nuked a couple of frozen burritos,” said Jake. “Of course, the precise origin of burritos isn’t known. According to Wikipedia, some speculate that they might have originated in the eighteen hundreds among the vaqueros, the cowboys of northern Mexico.”

Now Jake’s mother was staring at him, too.

“The ones in our refrigerator came from the grocery store,” she said. “They originated in the freezer section.”

“Riiight. Good to know. Well, I gotta run.”

“Say hi to Kojo for me,” said his mom. “Is he still fixated on that old TV show Kojak?”

Jake just nodded. He was afraid that if he said everything he somehow suddenly knew about Kojak—that the show aired on CBS from 1973 to 1978, with Telly Savalas starring as Theo Kojak, an NYPD detective whose catchphrase was “Who loves ya, baby?”—she’d want to take his temperature and then drag him off to see a doctor. Maybe a child psychiatrist. Not that the psychiatrist would be a child. After all, it takes eight years of post-undergraduate study to become board certified….

Jake forced himself to stop thinking.

He did okay until third period, when Mr. Lyons passed out a social studies pop quiz.

Everybody (except Kojo) groaned. But not Jake. He knew that the first permanent French colony in the New World had been Quebec, that the Philippines were named after King Philip II of Spain, and that Jacques Cartier had discovered the St. Lawrence River.

Jake knew everything. The answers to all twenty questions.

He completed the pop quiz in record time (ninety-three seconds) and was impressed by his much-improved handwriting. It looked like something you’d see on a really cool chalkboard at a coffee shop.

Mr. Lyons saw Jake just sitting there with his quiz sheet turned over on his desk. “Aren’t you even going to try, Jake?”

“I already finished, sir.”

Mr. Lyons sighed and held out his hand. “Let me see what you came up with this time.”

Jake turned in his test. Mr. Lyons scanned it quickly. Then he studied it more slowly. Then he smiled.

“Well done, Mr. McQuade. What did you eat for breakfast this morning?”

“Cheerios, sir. Which, by the way, used to be called Cheerioats between 1941 and 1945.”

“Is that so? Fascinating. Did you, by any chance, remember to bring your basketball uniform to school today?”

“Yes, sir. It’s in my locker.”

And Mr. Lyons’s smile grew even wider.

* * *

—

“Way to go, baby,” said Kojo when he saw that Jake had aced the pop quiz. “You got a hundred, just like me. I’m glad I could be such an inspiration to you.”

That afternoon, thanks to Mr. Lyons’s play diagrams and Jake’s practical application of geometry and trigonometry in the execution of those plays, coupled with his on-the-fly mathematical calculations of shot probability and a laser-sharp focus on the parabola, or curve, of all his shots—not to mention feeding the ball to Kojo at precisely the right instant so he could also score—the Riverview Pirates won their first game in five years.

All in all, it had been a pretty good day.

And Jake McQuade had no idea how he’d done any of it.

That night, Jake, Emma, and their mom sat down to dinner.

It was takeout from a local chicken place; Mom had grabbed the food on her way home from work.

“No events in the ballroom tonight,” she said, brushing back her hair. “Thank goodness. Dig in, guys. I got fried chicken for you, Jake. Salad for Emma. Rotisserie chicken for me. And mashed potatoes for everybody!”

Jake’s mom was in her early forties and very pretty. A lot of guys wanted to ask her out on dates. But she wasn’t interested. “One husband was enough for me,” she’d say with a laugh.

Like always, Jake used the bottom of his spoon to form a crater in his mashed potatoes. One that was deep enough to hold a pool of gravy. All of a sudden, it reminded him of the crater lake in the Philippines called Pinatubo, which was created after the 1991 eruption of the Mount Pinatubo volcano.

Why do I know that?

And why do I know that the Philippines is an archipelagic country consisting of 7,641 islands?

How do I even know the word archipelagic?

Suddenly he realized something: all this started happening after they had left the hotel. Did the ballroom speaker, the futurist guy, have something to do with what’s going on?

“So, Mom,” he said, trying his best to make sure his voice didn’t squeak, “exactly who was speaking at the hotel last night?”

“Dr. Sinclair Blackbridge,” she replied. “The place was packed. He’s a very famous technology prophet. His TED Talk, ‘Our Brilliant Tomorrow,’ has been watched nearly two million times online.”

“Dr. Blackbridge talked with some guy named Ted?” asked Emma.

Mom laughed a little. “No, Emma. ‘T-E-D’ stands for ‘Technology, Entertainment, and Design.’ Speakers at TED conferences give short, powerful talks. It’s all about spreading ideas.”

“And what idea was Dr. Blackbridge spreading last night?” asked Jake.

“He more or less repeated his TED Talk and predicted that the future, the world you two will live in, will be a very smart place.”

Jake nodded. It seemed like Dr. Blackbridge’s prediction might’ve come true. At least for Jake.

Dinner done and dishes cleaned, Emma and Jake went to their rooms to finish their homework. Actually, Jake had finished his in ten minutes after he got home, which was another major surprise. He usually didn’t bother with homework. He agreed with all those who said middle schoolers need extra sleep to grow and develop. He believed they also need extra video games. And extra time for texting.

But that night—in addition to the math, science, social studies, and ELA assignments he’d already nailed—he was going to do some research. He was going to watch Dr. Sinclair Blackbridge’s famous TED Talk.

He hoped it might offer some clue as to what the heck had happened to him at the Imperial Marquis Hotel.

Jake went to the TED website.

A quick sea

rch took him to Dr. Blackbridge’s famous lecture. He clicked play, and the video started streaming. Soon a very distinguished, silver-haired man in an open-collar white shirt and black suit strode onto a stage. He was wearing a microphone looped over his ear. The audience applauded eagerly.

After the ovation ended, Dr. Blackbridge went down the list of things he had successfully predicted in the past. Smartphones. Touch-screen computer control. GPS navigational devices in cars. Computers in classrooms. Intercontinental video calls over the internet. Toll gates where you didn’t have to stop to pay.

“So, what is my next prediction?” he asked his audience with a sly twinkle in his eye. “Well, it’s just that. A prediction. I’m nearly eighty years old, so I won’t be around to see it, because I am convinced it will take thirty, maybe forty, years before someone figures out precisely how to do it. But, my friends, the future will be all about IK. It will revolutionize everything. And what, you might wonder, is IK? Simple: Ingestible Knowledge.”

The crowd gasped. Jake did, too.

“For centuries, we humans have consumed information through our eyes and our ears. By reading. Or listening to lectures like this one. We can also learn a lot through our senses of smell and touch—like why one should avoid boiled cabbage or climbing thorny rosebushes.”

His audience chuckled.

“But our senses may not be the most efficient channel for learning. So here is my prediction: In the not-too-distant future, we are going to ingest information. You’re going to swallow a pill and know English. You’re going to swallow a pill and know geometry, trigonometry, and quantum physics. You’ll take another pill and instantly speak Swahili.”

Jake’s jaw nearly fell to his sneakers when Dr. Blackbridge said that.

“This will all happen,” the professor continued, “through the bloodstream. Molecules of knowledge will float up to your brain and deposit themselves in all the right cells and synapses. You won’t need to read a book or attend lectures to understand Shakespeare. The chemicals in these pills will do your learning for you.”

Mr. Lemoncello and the Titanium Ticket

Mr. Lemoncello and the Titanium Ticket Super Puzzletastic Mysteries

Super Puzzletastic Mysteries Sandapalooza Shake-Up

Sandapalooza Shake-Up Welcome to Wonderland #4

Welcome to Wonderland #4 The Smartest Kid in the Universe

The Smartest Kid in the Universe RING TOSS A John Ceepak Mystery Short (The John Ceepak Mysteries)

RING TOSS A John Ceepak Mystery Short (The John Ceepak Mysteries) Rolling Thunder (John Ceepak Mystery)

Rolling Thunder (John Ceepak Mystery) Don't Call Me Christina Kringle

Don't Call Me Christina Kringle Rolling Thunder

Rolling Thunder The Crossroads

The Crossroads Hell Hole

Hell Hole Beach Party Surf Monkey

Beach Party Surf Monkey Mad Mouse: A John Ceepak Mystery (The John Ceepak Mysteries)

Mad Mouse: A John Ceepak Mystery (The John Ceepak Mysteries) Mind Scrambler

Mind Scrambler Home Sweet Motel

Home Sweet Motel Riley Mack and the Other Known Troublemakers

Riley Mack and the Other Known Troublemakers The Island of Dr. Libris

The Island of Dr. Libris Escape From Mr. Lemoncello's Library

Escape From Mr. Lemoncello's Library The Black Heart Crypt

The Black Heart Crypt The Hanging Hill

The Hanging Hill Mr. Lemoncello's Great Library Race

Mr. Lemoncello's Great Library Race Riley Mack Stirs Up More Trouble

Riley Mack Stirs Up More Trouble Fun House (John Ceepak Mystery)

Fun House (John Ceepak Mystery) Whack A Mole: A John Ceepak Mystery (The John Ceepak Mysteries)

Whack A Mole: A John Ceepak Mystery (The John Ceepak Mysteries) Mr. Lemoncello's Library Olympics

Mr. Lemoncello's Library Olympics Tilt-a-Whirl jc-1

Tilt-a-Whirl jc-1 The Explorers’ Gate

The Explorers’ Gate The Smoky Corridor

The Smoky Corridor Ring Toss (john ceepak)

Ring Toss (john ceepak) Whack A Mole jc-3

Whack A Mole jc-3 Mad Mouse js-2

Mad Mouse js-2 Tilt-a-Whirl (The John Ceepak Mysteries)

Tilt-a-Whirl (The John Ceepak Mysteries) Free Fall

Free Fall Rolling Thunder jc-6

Rolling Thunder jc-6 Fun House jc-7

Fun House jc-7